Motorcycles reimagined

The world of motorcycling, along with the world at large, is at a turning point. Sticking to traditional methodologies and adhering to the status quo can leave a culture feeling stagnant and uninspired. Starting fresh, Hugo Eccles tapped into his wealth of industrial design experience to develop a bespoke visual language from an imagined alternate reality.

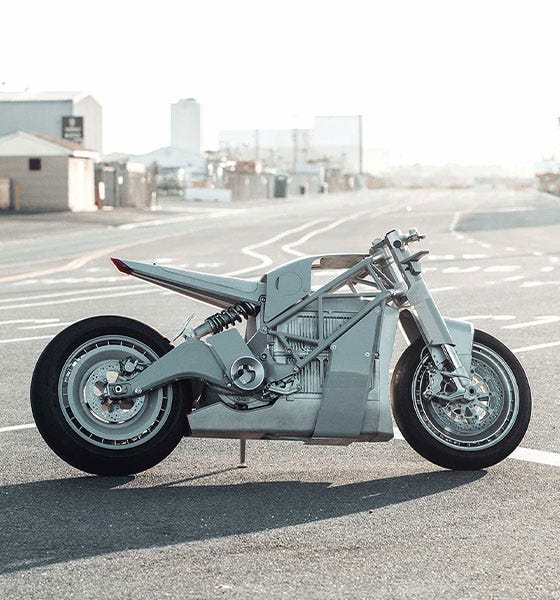

The XP Zero melds form and function, while simultaneously showing what is possible when one breaks away from preconceived notions and the limitations of what a motorcycle is supposed to look like.

Thank you for talking with us. We’re big fans of your work, especially the new XP. Let’s start with where untitled motorcycles began, and how you became involved.

Hugo Eccles (H.E.): My pleasure. My business partner, Adam Kay, started Untitled Motorcycles in 2010, right around the modern resurgence of the café racer custom scene. Adam’s and my paths crossed in 2013. I had just resigned from a director role at a well-known design agency in London and was about to move back to the United States.

I planned to start a custom motorcycle business in California and knew Adam from the Bike Shed [Ed. *Hugo and Adam are both founding partners of BSMC]. We started working together in London and, when the time came for me to move to San Francisco, I decided to create the American branch of Untitled Motorcycles, and UMC-SF was born.

Thank you for talking with us. We’re big fans of your work, especially the new XP. Let’s start with where untitled motorcycles began, and how you became involved.

I’m an industrial designer by trade. I earned my master’s degree at the Royal College of Art in London. I’ve been designing professionally for about 25 years and I’ve been a design director for 18 years.

The nice thing about industrial design is that it’s incredibly broad and varied, which has allowed me to work with the likes of TAG Heuer, Nike, Italian furniture brands, and consumer electronics companies. I’ve also created automotive concepts for Peugeot-Citroen and Ford Motor Company.

How have you applied those professional experiences into what you’ve created at untitled?

While I don’t have formal engineering or transport design training, I’ve had the privilege of working with many brands across almost every category of business. In a way, I’ve been working with motorcycle design elements for years - vehicle dashboard dials have parallels to luxury watches, furniture and their ergonomics are analogous to motorcycle seating, switchgear design is identical to user interfaces on consumer electronics, and so forth.

But the biggest value of my broad experience is that I can pull concepts from fields outside of motorcycling. If you’re designing a motorcycle and your only references are other motorcycles, it becomes an ever decreasing circle of inspiration – boundaries don’t get pushed if ideas aren’t being drawn inward from other places.

Fascinating, almost like reaching a point of diminishing returns in regards to creativity. touching on that circle of motorcycleculture and history, what were some of your early motorcycle influences?

I admired motorcycle and car design at an early age because of my dad. He was an amateur racing driver and dyed-in-the-wool petrolhead. I grew up in the English countryside and I remember my dad commuting to work on his metallic orange Suzuki GT250. He’d have his suit and tie on underneath his waterproof coveralls - very James Bond to my impressionable young mind.

And going back to pulling in ideas from outside sources, what are some other fields or industries that have influenced you creatively?

Car design is definitely where I draw some of my biggest influences. As a kid, my dad had a white Sunbeam Tiger - a small British car with a giant American V8 bulit by some guy called Carroll Shelby. The Tiger was, in many ways, the precursor to the AC Cobra.

Are there any standout designers you admire? What elements of their style do you appreciate?

I’m a huge fan of Marcello Gandini, who was the lead designer of the automotive design house Groupo Bertone. He was behind some amazing, audacious designs including the beautiful Lamborghini Miura and, five short years later, the groundbreaking Countach. The Countach’s mid-engine, cab-forward layout influenced all subsequent modern supercars. I recently visited the Museo Alfa Romeo outside of Milan which houses the Alfa Carabo - Gandini’s most outrageous creation and the epitome of the Wedge Era of car design - and it’s hard to believe the design is over half a century old.

I admired motorcycle and car design at an early age because of my dad. He was an amateur racing driver and dyed-in-the-wool petrolhead.

Speaking of creative works that last over time, are there ever times you are tempted to go back to past designs to revise, renew, or add-on to realize an original or evolving creative vision?

No project is perfect and that’s what drives you to do the next one. I might make small modifications or improvements to a project but I’m never tempted to fundamentally change it. A project is a representation of a moment in time, a sum of your decisions that you either made by choice, or were forced to make by circumstance, and it represents where you were in your personal and professional development. Every project has compromises, usually with a story attached, and that’s what gives it character. Because of my industrial design background, I always design with a view to batch production so, in a way, I do get to revisit projects when I build the next versions.

For example, I’m building a couple of new Hyper Scramblers for a client and I’m integrating all the insights from using the original Hyper Scrambler as my daily driver for the past four years: there are new parts that have been engineered and improved, plus new details that I wanted to include in the original.

My most recent project - the XP Zero - is probably about 60% of where my aspiration was. Certain ideas had to be put aside to get the bike to last year’s Goodwood Festival of Speed where it debuted. But, no worries, I’ll revisit them in the subsequent versions that I’m going to build.

Was that the most difficult part of the XP Zero build, not being able to execute 100% of your vision?

Yes, it was definitely a challenge, but it’s not completely unexpected. No real-world project is ever without compromises. I’ve found that the way around that is to make your aspirations so big that when you inevitably fall short the result is still good. Falling halfway to 200% is still a good result. Probably the biggest challenge with the XP project was in the early stages of the creative process where I had to un-learn everything I ‘knew’ about motorcycles and design from true first principles.

How so? What are the first steps in your process?

Hugo Eccles: I usually start a project with a full tear-down to the rolling chassis, and build it back up from there. I try not to be too dogmatic about what a build should be, instead I allow the shapes and intersections to dictate the form. For a build like the Hyper Scrambler, the iconic Ducati frame suggested the shape of the tapered fuel tank. The tank taper extended backwards to define the seat shape and forwards to form the vertical headlight - a pretty natural evolution. This method works well with a fuel-powered bike because necessary functional components - gas tank, exhaust, air intake system, and so on - are all opportunities for reduction and redesign.

With the XP project, however, as I started stripping everything off, I quickly realized there are only a few components that an electric motorcycle needs to have to work. You have the motor, the battery box, and, aside from the frame and wheels, not much else. The gasoline bike’s components that I’d normally use as a canvas for redesign just weren’t there. If I’m being completely honest, I had a bit of a crisis moment where I thought “there isn’t anything to do here.” I knew I didn’t want to just mimic the language of a gasoline bike with a ‘tank’ that had no real reason behind it.

Wow, quite the existential crisis. ow did you break through that?

From the outset, I knew that I didn’t want the XP to look like a conventional motorcycle because it isn’t conventional. If you make an electric bike look like a gasoline bike, you’re setting up a false equivalency and the expectation is that an electric motorcycle is just like a gasoline motorcycle but with a different motor in it. That’s just not the case.

The turning point was when I visited the Barber Motorsports Museum and saw their collection of turn-of-the-century motorcycles - marvellously varied machines that had been built with no preconceived ideas of what a motorcycle should be.

Those early inventors had to design their own solutions with no frame of reference, no rules, no ‘industry standard.’ I thought that our present situation with electric bikes had parallels with the dawn of gas bikes. I started thinking about what an electric motorcycle would look like if gasoline motorcycles had never existed. What would an electric motorcycle look like in 2020, with 135 years of only-electric motor history and development behind it? How would you design an electric motorcycle completely agnostic of gasoline?

To non-designers, at first glance, one would think not having limitations would be liberating, but it sounds like the lack of structure or goals could be daunting for a working professional in design.

You’d think no restrictions would be a dream for a designer, but it’s probably one of the things they fear most. It feels like you stare into the void, and the void stares back at you. To give me something to sink my teeth into, I started identifying certain ‘first principle’ motorcycle features. A key insight was that the rider needs something to grip with their knees for control while braking, accelerating, and cornering. The knee panels, and additional body-supporting surfaces like footpegs, seat, handlebars, I began to think of as ‘human control surfaces.’ I also started considering what ‘machine control surfaces’ might be. The XP can accelerate from 0-60mph in 1.6 seconds seamlessly, with no gear changes or pause in acceleration. The sensation is quite overpowering when you first experience it and feels like piloting a ground-based jet. I wanted to somehow embody that character in the design and looked at aerospace, MotoGP, and WTAC and other aerodynamic concepts for inspiration. The idea of ‘machine control surfaces’ became winglets, canards, and downforce structures that I integrated into the lines and shapes of the XP.

Is there any one part of the xp that stands out for people? One that tends to be a topic of discussion or critique more often than other parts of the bike?

Probably the most striking detail is the blade-like central CNC’d aluminum powertrain that the pilot rides on. The XP makes 140 foot pounds of torque - almost double the power of a conventional superbike - and I wanted to communicate that sense of power and excitement. Strangely, I get asked about the XP’s seat quite a lot because of its apparently extreme rake.

The visual rake is intentional to follow the angled form of the powertrain, but it’s also deceptive. The seat contains two different densities of foam which allows it to look angled but, when sat on, the soft foam gives way to a horizontal layer of firmer foam that supports the rider’s weight. All quite boringly practical and ergonomic.

Any parting advice for those wanting to get into what you do - whether that’s industrial design or custom bike building?

It’s important to be fascinated by the world and draw ideas from broad, non-motorcycle sources. I don’t think I would have tried half of the things I’ve done if I’d been formally trained as an engineer. After 25 years as an industrial designer, working alongside engineers, I do have a strong engineering intuition but, in some ways, my engineering ‘ignorance’ is one of my greatest assets. I regularly get asked how I achieved certain details on my builds and it’s often because I didn’t know they were ‘impossible.’ I just made them happen by some sort of positive willful ignorance. I always try to put myself outside of my comfort zone and some of my best work has come from being highly uncomfortable, not knowing how a project will turn out.

Nederland

Nederland  Italia

Italia  Deutschland

Deutschland  España

España  United Kingdom

United Kingdom  België (nl)

België (nl)  Belgique (fr)

Belgique (fr)  United States

United States  France

France  Sverige (en)

Sverige (en)  Danmark (en)

Danmark (en)  Österreich

Österreich  Portugal (en)

Portugal (en)  .COM (en)

.COM (en)